Growing Up in Miyazaki’s World: The Characters of The Boy and the Heron

Written by on Oct 24, 2025 12:00 PM

The return of visionary director Hayao Miyazaki marked a defining moment in modern animation. After a decade-long hiatus and what many believed to be his final retirement, Miyazaki crafted one of his most profound and deeply personal movies, The Boy and the Heron in 2023. The film’s universal themes, stunning artistry, and richly developed characters resonated far beyond longtime Studio Ghibli fans, captivating mainstream audiences worldwide and grossing over $280 million [1].

The Boy and the Heron invites viewers into a world where reality and fantasy are seamlessly intertwined, unfolding as a dreamlike odyssey that mirrors the inner journey of its young protagonist, Mahito. Set against the backdrop of World War II, the story explores loss, grief, and the painful beauty of growing up. Much like Chihiro in Spirited Away, Kiki in Kiki’s Delivery Service, and Ashitaka in Princess Mononoke, Mahito embarks on a path of self-discovery, navigating trauma through the lens of an immersive, surreal world that feels strange and deeply familiar.

Throughout his adventure, Mahito meets a cast of unforgettable characters who challenge him, comfort him, and reveal new layers of his own emotional landscape. Some guide him with quiet wisdom, others test his courage and sense of right and wrong, and many reflect the feelings he struggles to understand within himself. Each encounter nudges him closer to maturity, painting a rich emotional tapestry that is unmistakably Miyazaki. This attention to detail would earn the director an Oscar® for Best Animated Feature at the 96th Academy Award Ceremony, cementing his legacy as one of the greatest animators of our generation.

With The Boy and the Heron coming to Studio Ghibli Fest for the first time, we are diving into the film’s vibrant characters.

At the heart of the film is Mahito Maki (Luca Padovan), a 12-year-old boy, whose world is shattered by the death of his mother in a Tokyo hospital fire during the war. His grief manifests quietly but powerfully: he isolates himself, lashes out, and struggles to adjust to his new life in the countryside after his father remarries his late mother’s sister, Natsuko. This new environment is idyllic on the surface (lush forests, sprawling fields, a grand old house), but for Mahito, it’s haunted by the past and unsettled by the future.

Miyazaki crafts Mahito’s journey as an emotional odyssey mirroring his internal struggles. Early in the film, Mahito deliberately injures himself with a rock, a shocking moment that embodies the depth of his pain. He doesn’t yet have the language to express his grief; turning inward, withdrawing from those around him. This quiet storm within Mahito sets the stage for his encounters in another world shared by the living and the dead. An alternative reality where unresolved emotions take shape in physical forms.

Throughout this adventure, Mahito learns to navigate his grief not by escaping it, but by confronting it. He refuses to take over his great uncle’s mystical world, symbolically rejecting denial and isolation. Instead, choosing to return to reality, with all its messiness and pain. In true Miyazaki fashion, Mahito’s growth isn’t loud or triumphant; it’s subtle, bittersweet, and deeply human. By the end of the film, he has taken his first steps toward adulthood, not because his pain has vanished, but because he’s learned to live with it.

One of the most compelling characters Mahito meets is the Grey Heron (Robert Pattinson), a creature that begins as an unsettling trickster and evolves into an unlikely guide. At first, the Heron taunts Mahito, claiming his mother is alive and drawing him toward the abandoned tower. Its appearance—gangly, sharp-toothed, and unsettlingly human when its beak peels back—perfectly captures Mahito’s unease. The Heron embodies the ambiguity of grief: it tempts our protagonist with the hope of reversing loss, even as it unsettles him.

As the story progresses, the Heron sheds layers of its trickster persona, revealing a more complex being who assists Mahito on his journey. The Heron becomes a companion, albeit a sardonic one, guiding our hero through strange lands and dangerous encounters. Their relationship mirrors the classic Miyazaki dynamic between human protagonists and morally ambiguous companions, much like No-Face in Spirited Away or Calcifer in Howl’s Moving Castle.

Importantly, the Heron is not a benevolent mentor like a fairy godmother; he’s a reflection of Mahito’s own conflicting desires. At times, it pushes him forward, and at other times, it tests his resolve. The Heron’s duality underscores the idea that grief can both paralyze and propel us, tempting us to look backward, but also guiding us toward acceptance if we face it head-on.

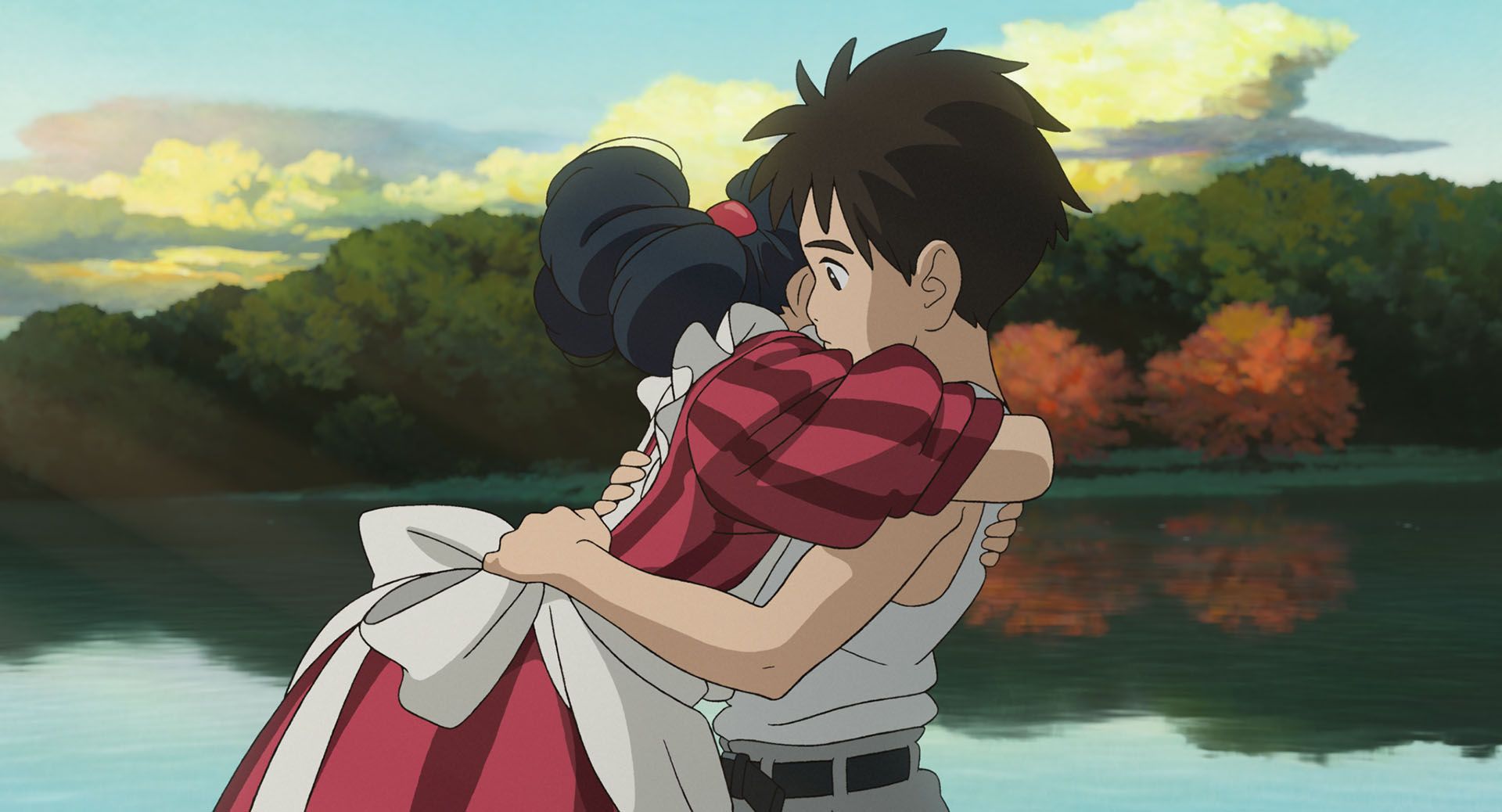

Himi (Karen Fukuhara), the young girl who wields flames with a serene grace, is one of the film’s most enchanting and emotionally resonant characters. Though her identity isn’t immediately clear, it is later revealed that she is a younger version of Mahito’s mother. This revelation reframes their bond: their friendship isn’t just another encounter; it’s a literal and metaphorical confrontation with his grief.

Himi’s warmth, courage, and kindness stand in contrast to Mahito’s guardedness. She embodies the innocence and strength his mother once offered him, guiding him through the strange realm and helping him navigate its dangers. When Mahito must part from her, the moment is laced with both tenderness and sorrow. He cannot stay in this world with her, nor can he reclaim the past.

Himi represents a pivotal stage in Mahito’s grieving process: the ability to remember the lost loved one not only with pain but also with love. Their companionship shows him that his mother’s presence isn’t entirely gone. It lives on in his memories and in the values she instilled in him. In many ways, Himi helps Mahito bridge the gap between childhood and adulthood, where memories of those we’ve lost become guides rather than weights.

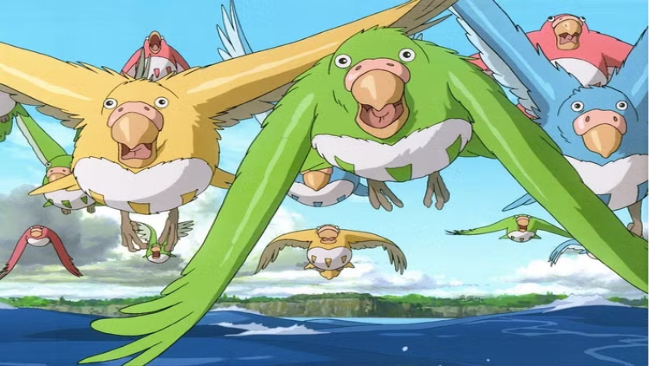

The Parakeets, both absurd and menacing, populate the fantastical world as militaristic, oversized birds that terrorize those around them. Their exaggerated behavior and towering forms inject a surreal, almost comic-book sense of danger into Mahito’s journey. But beneath their bizarre exterior, the Parakeets represent forces that Mahito must confront (fear, chaos, and the abuse of power).

Miyazaki often uses creatures to reflect the real-world horrors that children must navigate. In The Boy and the Heron, the Parakeets’ militarism and aggression evoke the specter of war— a force that has already profoundly shaped his life. Their world is crumbling; they vie for control over the tower and its magic. Mahito’s encounters with them force him to act decisively and courageously, pushing him to shed the passivity that has characterized his grief.

By facing the Parakeets and helping protect those vulnerable to their violence, Mahito steps into a more active role in his own story. He is no longer the boy watching helplessly as the world burns; he becomes someone who can shape his destiny, even in the face of overwhelming forces.

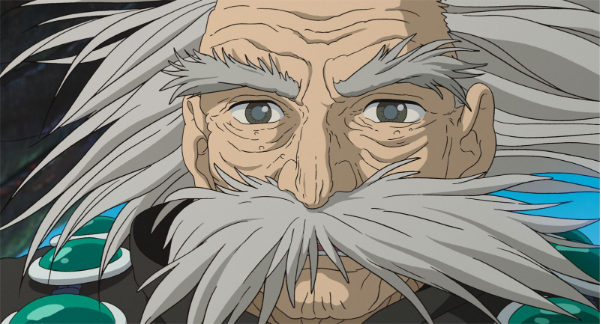

Deep within the tower, Mahito meets the Great Uncle (Mark Hamill), a wizardly figure who built the dreamlike world and now guards its fragile balance. The Great Uncle’s offer to Mahito—to inherit the world and keep it in balance, serves as the emotional and moral climax of the story. It’s a test, not just of Mahito’s courage, but of his willingness to let go of fantasy as an escape.

The Great Uncle represents the weight of legacy, responsibility, and the temptation to withdraw from a painful reality. Accepting his offer would allow Mahito to remain in a world where grief can be suspended, where he could cling to the past through illusion. Rejecting it means returning to the real world with all its imperfections, uncertainty, and sorrow.

Mahito’s refusal to inherit the tower mirrors his emotional growth: he chooses life over stasis, reality over fantasy. It’s a deeply mature decision, one that echoes Miyazaki’s recurring theme that growing up involves accepting the inevitability of loss while finding meaning in moving forward.

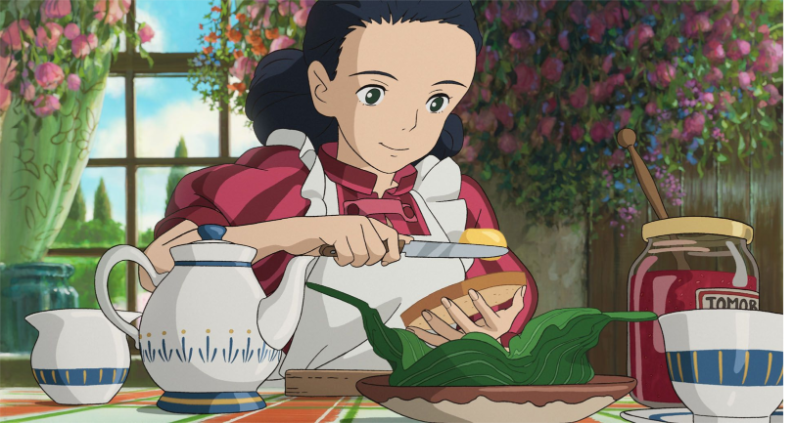

While the otherworldly creatures drive much of the narrative, the real-world figures (Natsuko (his father’s new wife and his late mother’s sister) and the elderly household helpers) play crucial roles as emotional anchors. Natsuko’s pregnancy and her fragile health give Mahito a tangible reason to confront his fears and step into responsibility. His decision to save her when she’s kidnapped by supernatural forces shows his shift from grief-stricken child to protective older brother-to-be.

Meanwhile, the household helpers, with their humor and loyalty, offer Mahito a sense of stability and community. Their presence, though understated, grounds the story in human connection—a reminder that even as Mahito ventures into surreal worlds, his real growth happens in his relationships with those around him.

Much like other Studio Ghibli films, The Boy and the Heron isn’t just another adventure; it’s an intimate portrait of a boy learning to live with loss. Each character Mahito encounters reflects a facet of his emotional journey: the Heron mirrors his conflicted feelings; Himi embodies love and memory; the Parakeets represent chaos and fear; the Great Uncle tempts him with escape; and the real-world figures anchor him in the present.

Through these encounters, Mahito undergoes a transformation that is both personal and universal. He learns, as so many Miyazaki protagonists do, that growing up means facing the pain of reality without losing one’s capacity for wonder. Grief doesn’t disappear; it evolves, becoming part of who he is.

Sign up for our newsletter to keep up to date with all our screenings.

"*" indicates required fields